Diplomats for sale: How an ambassadorship was bought and lost

Get our headlines on WHATSAPP: 1) Save +1 (869) 665-9125 to your contact list. 2) Send a WhatsApp message to that number so we can add you 3) Send your news, photos/videos to times.caribbean@gmail.com

The story of Ali Reza Monfared, the Iranian who tried to buy diplomatic immunity after embezzling millions of dollars.

by Kevin Hirten

![Dominican Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit (left) and Ali Reza Monfared, the man who bought a diplomatic passport [Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2019/12/2/ed9c7c56c2b340ce9eb82bb9ba859027_18.jpg)

So, when he fell from his trademark sartorial splendour to the light-blue uniform of Iran’s notorious Evin Prison, the contrast was harsh.

His neatly combed hair has also greyed considerably since Iranian International Police arrested him at a Caribbean resort in 2017.

In November 2019, Monfared was convicted of embezzling millions of dollars from his country, just one of the strands in a global web of financial, diplomatic and personal fraud that saw him sentenced to 20 years in prison and a $1.3bn fine.

It could have been worse. In 2016, Monfared’s billionaire business partner, Babak Zanjani, was sentenced to death for his role in the siphoning off of $2.8bn from Iranian oil revenues.

If you want to learn more about the legal trade of passports and some of the pitfalls, check our podcast Al Jazeera Investigates: Diplomats for Sale.

Monfared’s natural charisma and hustle had taken him far. From humble beginnings in the home decoration business, he had rocketed to success: banker, international oil trader and, finally, “His Excellency Dato Ali Reza Monfared”, Dominica’s ambassador to Malaysia.

In 2015, Monfared had secured a Dominican diplomatic passport and, with it, what he treasured most of all – diplomatic immunity.

A charismatic outsider

In 2012, Monfared arrived on Labuan, a small Malaysian island off the coast of Borneo, as a charismatic outsider with big ambitions.

“You would practically fall in love with him because he is such a sweet talker. Ali can convince anybody into doing anything,” said Manoj Bhullar, the owner of a marine logistics company on Labuan. He refers to Monfared as “Ali” because they were once best friends.

When they met in 2012, Monfared claimed to be an agent of the Iranian government, working, under the direction of Babak Zanjani, to move oil from Iran.

As Iran was under sanctions, “they had problems”, Bhullar explained.

When Bhullar proposed a solution to those problems, it marked the beginning of a relationship that would change his life.

The Bhullars

I first heard about Monfared in the summer of 2018. I was interested in the sale of diplomatic passports in the Caribbean and had started gathering sources through a contact connected to Bhullar’s wife, Kiran. She and her husband had been swindled by Monfared and Kiran would text me long threads about their quest for justice.

Her story was compelling, so I asked to meet in person. But while it was clear she wanted to speak, she seemed reluctant to meet.

She eventually agreed, but made no promises. So, with correspondent Deborah Davies and cameraman Manny Panaretos, I travelled to Kuala Lumpur without a guarantee of an interview.

We met the Bhullars for lunch at a shopping mall.

Have a tip for Al Jazeera that should be investigated? Find out how to get in touch with us on our Tips page

“You draw up a mental picture of the people you’re going to meet,” Davies said afterwards. “[Then] in walks this really stylish, charismatic, fabulous-looking couple.” It was easy to see how the Bhullars would have fit in with Monfared’s glamorous lifestyle.

Bhullar later told me that he also had a mental picture of how the lunch would play out: He would sit down, shake our hands, politely decline to talk and then walk out.

But that was not what happened.

Instead, the couple unburdened years of pent-up frustration and regret over their dealings with Monfared.

As our meeting entered its third hour, the conversation turned to Labuan. I told them I had often heard it described as the Cayman Islands of Asia, because of its flexible financial rules and many shell companies. I had wanted to visit but had been told that, as a reporter, it would be impossible.

The Bhullars dismissed my concerns and invited us there. “It’s my island,” joked Bhullar. And from the moment we arrived, it did feel that way.

Labuan

Labuan is the best natural harbour in Borneo. In fact, it means “harbour” in Malay. That is why people have been fighting over it for years. The Japanese took it during the second world war and many Allied soldiers died trying to recapture it.

This is not history to Bhullar, it is family lore.

“My granddad, he was involved in the Punjab Regiment … Sixty-seven of them were sent into Labuan to fight the Japanese all by themselves. Only four survived. My granddad was one of them,” he explained.

His grandfather decided to stay.

Standing on the jetty in Labuan, Bhullar was at home and at ease. Gone was the troubled businessman we met in Kuala Lumpur.

“From a young age, dad got us interested in the sea,” he explained. “He had a boat. He would ask us to jump off this wharf here and we had to swim all the way to the island up there.”

Bhullar’s marine services business was doing well when Monfared arrived on the island. And, for a while, business got even better as Monfared tried to find a way around the sanctions on Iranian oil.

Al Jazeera reporter Deborah Davies with Manoj and Kiran Bhullar [Kevin Hirten/Al Jazeera]

It was Bhullar who offered him a solution. He had learned of a small loophole, or at least an untested area, in the law: If oil was stored offshore for a certain period of time, it ceased to be oil from the country of origin and became “Malaysian” oil. And there were no sanctions on that.

It was not long before Monfared and Bhullar were running a massive supply and storage operation from Labuan harbour.

“Ships would come in from Iran … We had oil tankers parked right outside here. The mother tanker would come in, discharge their oil onto our tankers and they would go off and we would have oil stored all off on the bay here,” Bhullar explained.

“Each tanker would bring in … one million to two million barrels.”

His company had eight storage units all around Malaysia, where they waited for the ships to arrive so they could siphon the stored oil and sail on to China, where it was to be sold

For a time, it worked. Bhullar did the marine logistics and Monfared handled the money. Then, in 2013, Zanjani was arrested.

The operation shut down, but the Bhullars and Monfared remained close friends, sharing family meals and holidays.

A small-town financial hub

To understand the tangled relationships that ruined the Bhullars’ lives, it helps to understand Labuan.

First of all, it is small – about 93 square kilometres (36 square miles). The southern half of the island is the most developed, with a few high-end hotels that host oil workers and international businessmen. Overlooking the harbour, in the centre of the downtown area, is a towering financial complex that is home to more than 6,500 offshore companies.

It is an ideal location for an operator like Monfared: It is out of the way, the island’s economy is heavy on international finance, oil and gas, it has a low tax rate and it operates under the protection offered by Malaysia, meaning that it benefits from Double Taxation Agreements – an assortment of tax exemptions – signed with 70 other countries, according to consulting firm Dezan Shira & Associates

It is simultaneously a financial hub and a small town.

I kept thinking why should you be afraid, if you’re not guilty?

MANOJ BHULLAR

Labuan’s easy sense of community may explain why Kiran found it so hard to believe that Monfared was up to no good. “He was very sweet to everyone, he always called me his sister,” she explained.

“He was closer than a family member,” Bhullar added.

When Zanjani was arrested, Bhullar said Monfared was scared. “I kept thinking why should you be afraid, if you’re not guilty?”

But as the outlines of the oil scheme and embezzlement became clear to the Bhullars, they understood that their friend was in trouble.

The Commonwealth of Dominica

By the summer of 2014, Monfared had temporarily relocated to Spain. Still, the Bhullars remained close to him and, in August, the two families holidayed together in Panama. It was during that holiday that Monfared proposed that he and Bhullar take a quick side trip to the Commonwealth of Dominica.

“Just before landing at the airport, while we were still in the air, that’s when Ali told me the reason. He has applied under a programme to get him and his whole family citizenship.”

Dominica is an island in the Lesser Antilles – a vertical strip of eastern Caribbean islands that cascades towards South America. It is volcanic and wild, with steep peaks jutting dramatically out of the sea. But lacking the picture-perfect beaches of its neighbours, it struggles to attract tourists and is one of the poorest countries in the region. It is also one of those least touched by development.

It can take roughly 90 minutes to reach the country’s capital, Roseau, from the airport. Winding through the narrow mountain roads, Bhullar said he was impressed by the tropical air and lush scenery. It reminded him of home. But, while he was still in holiday mode, Monfared was all business, preparing for a meeting the following morning with the country’s Citizenship by Investment (CBI) minister.

Monfared’s goal was to secure citizenship for his family. It is perfectly legal and very common, usually costing between $200,000 and $300,000. The money either goes to private projects, like hotels, or to infrastructure. It can be a huge source of revenue for small Caribbean islands.

On the cab ride from the airport, Bhullar talked to the driver. As a fellow islander, he recognised the problems the driver outlined: periodic shortages of food, water and electricity.

Bhullar helped prep his friend for the next day’s meeting.

“I just told Ali … ‘In your meeting … what they will ask you is simple, what benefit are we going to get from giving you the citizenship?'”

Monfared suggested offshore banking, but Bhullar urged him to play up basic island essentials, which he did.

In his meeting, Monfared floated several investment ideas, including aquaculture and geothermal energy projects. All of this came with the promise of strong business and political ties to the Malaysian government.

Bhullar recalled that “Ali came screaming back to my room at 10:30 in the morning and he said ‘Get ready!'”

“I said ‘Why, what’s happening?'”

“He said, ‘I’ve said what you asked me to say and they’ve asked me to explain. I know nothing to explain and I’ve informed them that my business partner … is here, he will explain to you.'”

Bhullar was rushing to get dressed when Monfared added that the meeting was not with ministers any more; it was with Dominica’s prime minister, Roosevelt Skerrit.

“I went to the Caribbean in my shorts and T-shirts. I had to borrow a shirt and pants from the front desk,” he said, recalling the absurdity of the situation.

Bhullar has a picture of the three of them meeting in the prime minister’s office that day, Bhullar in an ill-fitting shirt.

From left to right: Ali Reza Monfared, Dominican Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit and Manoj Bhullar [Manoj Bhullar/Al Jazeera]

Towards the end of the meeting, Bhullar received his second shock of the day. Bhullar said Skerrit made an offer, not to Monfared, but to him.

“He said ‘Why don’t you be our ambassador at large?'”

“I said ‘No, I’m a businessman, not a politician,'” Bhullar explained.

Prime Minister Skerrit told Al Jazeera that he has no memory of this meeting.

Back at their hotel, Bhullar said Monfared had an idea: “Convince them that I can do the part.”

According to Bhullar, the following morning, he and Monfared had breakfast with the CBI minister, Emmanuel Nanthan. Bhullar recommended Monfared for the ambassador post and Nanthan seemed satisfied with that, as long as it brought much-needed investment to the island. The final decision on such matters is up to the prime minister, however.

Things moved quickly after that. Monfared had his meetings in Dominica on August 26, 2014. A week later, he had registered three companies there.

On September 3, his family received its naturalisation paperwork and he became a citizen of the Commonwealth of Dominica.

My Dominica Trade House

One of the first things Monfared did when he returned to Malaysia in September 2014 was to start a new company, with the Bhullars as partners.

On the face of it, the company was about facilitating trade and investment between Malaysia and Dominica. In reality, it was about getting Monfared a diplomatic passport.

Within a month, Dominican government officials were visiting Malaysia, all expenses paid. The funds were coming from the coffers of the new company, My Dominica Trade House.

Bhullar showed us a large green book that detailed the brief but storied history of a company so notorious it would one day become the title of a political protest calypso song. The glossy photos inside showed a series of fancy receptions for prominent Dominican delegates, smiling and toasting with a beaming – and impeccably dressed – Monfared.

We don’t use the word bribe … But, definitely … without that money, Ali would not have got his diplomatic passport.

MANOJ BHULLAR

It was not long before Monfared bought a property befitting his new role as a prospective ambassador. The Bhullars say it was paid for by the company. Located on a lake in an upscale neighbourhood of Kuala Lumpur, it would become Monfared’s embassy.

By mid-October 2014, Monfared had received his official application for a diplomatic passport and, shortly after, requests started to come in for payment. The point person for this was Minister Nanthan.

Bhullar said Monfared had understood that his diplomatic credentials would entail some payments to Dominica. But they quickly exceeded his expectations.

On October 29, 2014, two emails arrived with two invoices for help with Skerrit’s upcoming election campaign. One was for $85,000 to print the party’s manifesto. The other was for $115,000 for billboards, a sound system and fireworks.

A screenshot of the now-defunct My Dominica Trade House website [Al Jazeera]

But they were not all campaign-related payments. In November, Nanthan asked for another $200,000.

Bhullar was in charge of arranging the payments and recalled how there was a delay to this one. “We had a problem to transfer the money into his company’s account, which is the petrol service station in Dominica,” Bhullar said. “It took us almost four to five days.”

According to emails provided to Al Jazeera, the $200,000 payment was sent to a bank account for a service station owned by Nanthan’s family in Portsmouth, in the far north of Dominica.

Nanthan was annoyed when the money did not arrive on time. In an email, he wrote: “I am still waiting on routing instructions. This is taking forever. I must say this lacks the efficiency displayed to me by Dato Ali and his organization. I am extremely disappointed.”

“Oh, we were getting emails, phone messages, phone calls. He kept, you know, insisting … ‘when are we getting the money?'” Bhullar recalled.

There are plenty of pictures of Nanthan in the big green book.

“We don’t use the word bribe … But, definitely … without that money, Ali would not have got his diplomatic passport,” Bhullar said.

In early December, five months after the initial meetings in Dominica, Monfared received what he had been hoping for – a signed letter from the prime minister offering an ambassadorship.

The appointment raises questions, not only because it happened immediately after an election he helped pay for, but also about the due diligence the Dominicans carried out because by this point Monfared’s business partner, Zanjani, had been arrested and the First Islamic Investment Bank, of which Monfared was the authorised signatory, had been sanctioned by the US and the EU.

Monfared sent his “voluminous thanks and appreciation” to Skerrit, promising to “steadfastly develop the bilateral relationship and diplomatic ties between the Commonwealth of Dominica and Malaysia”.

The next step was to plan the biggest party yet, to welcome the prime minister to Malaysia. Skerrit wanted the company to pay for him to travel to Malaysia and then on to meetings in China by private jet. Monfared agreed.

In March 2015, Skerrit touched down in Malaysia. No expense was spared. He was picked up from the airport in a Rolls Royce. The reception for him featured champagne, catered food and a jazz band. It was there that Skerrit handed Monfared his diplomatic passport.

Dominican Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit, left, and Ali Reza Monfared [Al Jazeera]

Ambassador Monfared

“After he got [his] diplomatic passport, he totally changed his attitude,” Kiran said.

“I couldn’t call him Ali any more,” explained Bhullar. “He’d say ‘No, you’ve got to call me Excellency.'”

Monfared was open with Bhullar about why the diplomatic passport was so important to him. “He said to me … ‘I get diplomatic immunity … I don’t have to be worried about the Iranians.'”

One night at the My Dominica Trade House offices, Monfared had his first opportunity to test the power of his diplomatic passport. The police responded to allegations of drug use at a party in the office.

Bhullar recounted how he watched as two police vans with about 20 officers in them pulled up outside. According to Bhullar, Monfared hid behind a door, waving his diplomatic passport and saying: “You can’t arrest me, I’m a diplomat.”

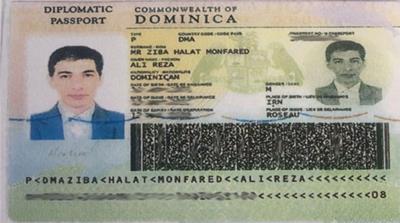

Ali Reza Monfared’s Dominican passport [Al Jazeera]

“I asked them [the police] ‘What happened? Did you find any drugs?'” Bhullar explained. “The police said, ‘Oh we couldn’t go into the room. He’s a diplomat … This is out of our jurisdiction.'”

In addition to giving him a newfound sense of invincibility, the Bhullars said the passport seemed to encourage all sorts of erratic behaviour.

Monfared had a lake behind his house where Kiran said he wanted to create a bird sanctuary. She said he ordered 1,500 ducks and caged macaw parrots and other birds.

The ducks, she said, would roam through the neighbourhood. “Complaints kept coming in, non-stop.”

Game over

By December 2015, Monfared’s luck was running out.

Zanjani’s trial had started and the Iranians had issued an arrest warrant for Monfared. The Malaysian authorities picked him up, but his diplomatic passport, quite literally, got him out of jail.

“He was released on condition that he was not supposed to leave the country and his home,” Bhullar explained.

Monfared decided to save himself by betraying his friend. He sold the property – which the Bhullars say belonged to the company – and, using his diplomatic passport, escaped to Dominica, leaving the Bhullars with his debts.

“It was a horrible time,” said Kiran, explaining how her family’s reputation was destroyed, their savings wiped out and her husband arrested for a time.

The police said, ‘Oh we couldn’t go into the room. He’s a diplomat … This is out of our jurisdiction.’

MANOJ BHULLAR

In Dominica, Monfared quickly overstayed his welcome after his lavish lifestyle ran up unpaid bills. After six months, he left for the Dominican Republic, where he hid out at a beachside resort town called Boca Chica.

Back in Malaysia, the Bhullars had heard that Monfared left Dominica, but no one knew where to. Then, one day, Bhullar noticed that Monfared’s Malaysian lawyer had posted on Facebook that he had checked into a resort in the Dominican Republic

“I sent [a local cab driver in Boca Chica] some money. I said, ‘Here you go, $200, go up to this resort and see if you find a guy by the name of Ali Reza Monfared, an Iranian man,'” Bhullar explained.

The cab driver confirmed that Monfared was there.

Bhullar called the Iranian authorities. Shortly after, Monfared was picked up and transported to Iran.

“[It was] bittersweet,” said Bhullar. “[But it felt] very much [like] justice.”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA NEWS

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.