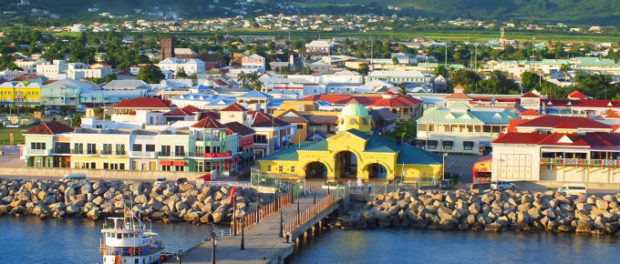

© Provided by Ozy Media, Inc.Tall and well-groomed, Brian Richards has eyes that smile when he talks about the fellowship he says exists between Chinese immigrants and Trinidadians of African or Indian descent at the Grace Chapel church in the heart of Port of Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago. Richards, in his mid-30s, has for the past three years been pastor of the church, home to a Chinese Christian Fellowship congregation where 50 members regularly meet. But look beyond the church, and things appear less rosy.Small Chinese businesses are cropping up throughout the Caribbean, bringing with them concerns ranging from who they employ to whether they adhere to local standards and laws. Chinese immigrants usually open family-run businesses where they employ other workers from China, instead of locals, says Ramchand Rajbal Maraj, president of the Couva/Point Lisas Chamber of Commerce in Trinidad. On the other hand, he concedes, they do provide significant rental income to locals. Dwyer Astapahan, a businessman and former government minister in the neighboring island nation of St. Kitts and Nevis, is clearer: Chinese immigrant businesses are hurting his country. Where they all agree is that the Caribbean is witnessing a silent flood of new Chinese immigrants that’s showing no signs of abating.

© Provided by Ozy Media, Inc.Tall and well-groomed, Brian Richards has eyes that smile when he talks about the fellowship he says exists between Chinese immigrants and Trinidadians of African or Indian descent at the Grace Chapel church in the heart of Port of Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago. Richards, in his mid-30s, has for the past three years been pastor of the church, home to a Chinese Christian Fellowship congregation where 50 members regularly meet. But look beyond the church, and things appear less rosy.Small Chinese businesses are cropping up throughout the Caribbean, bringing with them concerns ranging from who they employ to whether they adhere to local standards and laws. Chinese immigrants usually open family-run businesses where they employ other workers from China, instead of locals, says Ramchand Rajbal Maraj, president of the Couva/Point Lisas Chamber of Commerce in Trinidad. On the other hand, he concedes, they do provide significant rental income to locals. Dwyer Astapahan, a businessman and former government minister in the neighboring island nation of St. Kitts and Nevis, is clearer: Chinese immigrant businesses are hurting his country. Where they all agree is that the Caribbean is witnessing a silent flood of new Chinese immigrants that’s showing no signs of abating.

China’s excess capital has focused global attention on the heavy investments – from stadiums to highways – its government is making in small nations everywhere. But in the Caribbean, there’s also a parallel invasion quietly underway: thousands of Chinese individuals are wading into the region, setting up small businesses and supermarkets, and reshaping the economies and societies of a region traditionally closer to the West and Taiwan.

A Chinese-owned restaurant in Curepe, Southern Main Road, Trinidad.” data-id=”77″ data-m=”{“i”:77,”p”:75,”n”:”openModal”,”t”:”articleImages”,”o”:2}”>

[These are] people who came specifically to open up shops, so their impact is much more than you would imagine by the numbers.

Cecilia Green, Syracuse University

Dominica, St. Vincent, St. Kitts and Antigua – each with populations ranging from 16,000 to just over 100,000 – now host between 200 and 300 Chinese migrants, says Cecilia Green, an associate professor at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School who has recently researched the subject. Dominica’s president, during a 2015 visit to Beijing, publicly wooed Chinese immigrants and investors to his nation.

“This is entrepreneurial migration, not people seeking work,” says Green. “[These are] people who came specifically to open up shops, so their impact is much more than you would imagine by the numbers.”

That impact is beginning to be noticed as far away as Washington, where the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agriculture Commission has in at least one report noted the growing presence of Chinese-owned supermarkets in the region’s largest and richest country, Trinidad and Tobago.

For sure, Trinidad has had earlier waves of Chinese migration. Official records show the first Chinese migrants arrived in 1806, followed by a migration after slavery was abolished and then again, as China sank into turmoil in the early 20th century. And recent Chinese infrastructure projects in the region have brought hundreds of workers to the Caribbean too.

But Green says the new migrants should not be confused with those working on such projects financed by the Chinese government, who usually return home at the end of their contracts. So recent is the “phenomenon of the new Chinese entrepreneurial enclaves in the Eastern Caribbean” – no older than 15 to 20 years – that little has been published about it, says a 2015 book Green co-authored.

Maraj agrees. Initially, he says, “it was a bit off and on, not too rapid until the last five years when you have an increase in the number of Chinese businesses…car dealerships, casinos, supermarkets, restaurants.” China’s own internal changes – the dismantling of some state-supported benefits and job security – may have contributed to pushing entrepreneurial Chinese to look for opportunities elsewhere, suggests Green. While migrants to the global north were mainly “professionals and students,” it’s mostly “entrepreneurial migration” to the global south, she says.

Provided by Ozy Media, Inc. Elder William Allum Poon, an unidentified Chinese

congregation member, and Pastor Brian Richards of the Grace Chapel church, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago.At Grace Chapel Church’s Chinese Christian Fellowship, Elder William Allum Poon – who came from Hong Kong – says most immigrants from China have stayed on because they prefer Trinidad to the home they left. “They came here because of work and to have another lifestyle. Here is freer than in China,” he says. Most members in his congregation are in their forties, who came to Trinidad on visas, liked it, and decided to stay, opening up restaurants and supermarkets, he says.

It’s a decision Richards, the pastor, welcomes. “To me, the Chinese community is very welcoming, friendly,” he says. “The relationship is pretty amicable, no tensions” between his Trinidadian congregation and the Chinese congregation that share the same hall, he adds.

But many in the business community across the Caribbean see it differently. By mostly hiring fellow Chinese workers, these new businesses aren’t creating jobs for locals, they argue. Many in the local private sector also “see them [the Chinese] as competing with them,” says Green. Yes, some have benefited from renting out properties – Chinese who run casinos pay about TTD40,000 [US$5,954] a month, while small groceries pay TTD25,000 [US$3,721], says Maraj. But that too has come at a cost for others, in the form of rising rental rates for local entrepreneurs as landlords “jack up their prices,” says Green.

In St. Kitts, Astaphan says the Chinese “have crowded out the local small retail outlets completely.” He accuses Chinese businesses of selling predominantly “inferior goods.” These businesses, he says, “bring in Chinese workers that are for all practical purposes slave labor and they pay below the minimum wage here, so locals are deprived of jobs.”

The growing Chinese entrepreneurial community in the Caribbean is by no means monolithic. As China grows wealthier, the Caribbean’s limitations in size are making a few return home, says Green. Better-off Chinese entrepreneurs here are sending their children to North America for studies, and it’s unclear how many will come back to the Caribbean.

But all signs suggest they’ll be replaced by fresh Chinese migrants to the Caribbean. About 43 percent of all applicants to Antigua’s Citizenship by Investment program since its start in 2014 are Chinese, for instance. That regional spread of Chinese investors and immigrants worries Astaphan. “I cannot see any positive impact of their presence,” he says.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.