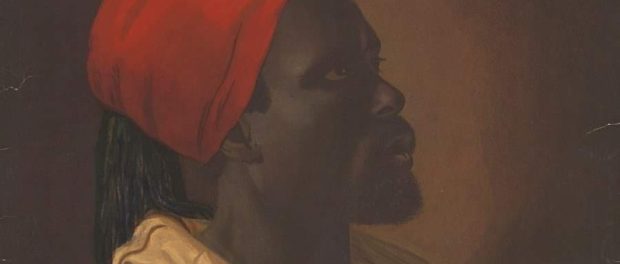

Toussaint Louverture: The Slave Who Defeated Napoleon And Led The Haitian Revolution

Get our headlines on WHATSAPP: 1) Save +1 (869) 665-9125 to your contact list. 2) Send a WhatsApp message to that number so we can add you 3) Send your news, photos/videos to times.caribbean@gmail.com

The heroic story of Toussaint Louverture, who brought himself and his people from slavery to freedom.

A typical 18th-century plantation employed hundreds of slaves who worked 16 to 18-hour days in all kinds of weather. Rations were minimal and punishments were brutal. The largest, most profitable European slave colony was French-controlled Saint-Domingue, the western part of contemporary Haiti (the eastern part, Santo Domingo, was Spanish).

Famed economist Adam Smith described Saint-Domingue as “the most important of the sugar colonies of the Caribbean,” and largely due to trade with the newly independent United States, production in Saint-Domingue nearly doubled between 1783 and 1789.

The French colonial powers thus made sure to maintain control over the more than half a million black slaves in Saint-Domingue — and to that end, they employed horrific violence.

In their book Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492-1971, Robert and Nancy Heinl quote Vastey, a slave who described the crimes against the slaves of Saint-Domingue:

“Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive…. flayed them with the Lash…. lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes…thrown them into boiling caldrons of cane syrup…put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss…consigned these miserable blacks to man-eating dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with bayonet and [dagger]?”

Despite — and perhaps because of — such violence, Saint-Domingue saw a steady succession of slave revolts beginning as early as 1679. This would continue into the 18th century when in the last years before the French Revolution (1785-1789), the French brought 150,000 slaves to Saint-Domingue to keep up with the region’s explosive economic growth.

This growing number of slaves grew angrier at the conditions they faced, and colonial powers took note of it. As the Marquis de Rouvray wrote in 1783: “We are treading on loaded barrels of gunpowder.”

Slave Revolt

Wikimedia Commons“Burning of the Plaine du Cap – Massacre of whites by the blacks.” A French military rendering of the August 1791 slave revolt.

On the night of August 21, 1791, the barrels exploded. The slave revolt spread fast, giving rise to numerous armed rebel bands. At first, the African rebels did not fight for full emancipation; in fact, most generals sought only freedom for themselves and their followers and better conditions for other slaves.

Then, two factors transformed the conflict into something greater and further reaching: the French government’s desperate need for allies, and the leadership of one slave named Toussaint Louverture.

The French Revolution And Counter-Revolution

By 1793, the French revolution had fallen in the hands of the Jacobins, among the most radical of the revolutionary groups. French Royalists, the British, and the Spanish all fought against the Jacobins, and eventually, the revolution would yield to more moderate leadership, and then to the reign of the autocratic emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821).

In spite of its maxim of “liberté, égalité, and fraternité,” it was only in the Jacobin government’s dying moments (February 1794) that it abolished slavery. And this only happened because three abolitionists from Saint-Domingue — a white colonist, a mulatto, and a black freedman — managed to make it to Paris and demand it. In the throes of revolution and in need of support, the fiery Jacobins granted the petition for abolition without debate.

Their acquiescence proved fruitful: the support of the 500,000 slaves and the economic base they represented in Saint-Domingue allowed the Jacobins to continue fighting their other enemies in the revolution. And the most important leader among this population of slaves would soon prove to be none other than Toussaint Louverture (also known as Toussaint L’Ouverture).

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.