One of the world’s biggest reggae stars, a Grammy award-winning artist from Jamaica with more number-one singles than legend Bob Marley, has been locked inside a U.S. prison for nearly a decade.

Buju Banton is set to be released in a matter of months, but the cocaine-trafficking case against him still infuriates his most ardent supporters, who believe he landed behind bars after being set-up and seduced by a U.S. government informant.

“He was entrapped. Just follow the case,” one longtime fan, 55-year-old Alvin Walfall of Bowie, Maryland, said. “It was entrapment.”

Walfall is one of nearly 5,000 people who signed onto a series of online petitions calling for Banton’s freedom and questioning the case against him.

For years, U.S. officials demanded that a key piece of evidence — undercover video from Banton’s last meeting with the informant — stay under seal, hidden from public view. But ABC News appealed to a federal judge, and the video has now been unsealed.

It offers the most complete account of how Banton, 44, ended up in a U.S. prison, convicted of two counts for his role in a conspiracy to sell cocaine.

But Banton has maintained his innocence, insisting he never intended to go through with a drug deal and was only guilty of “running my mouth.”

Banton is a prolific dancehall artist, known around the world for his aggressively gruff voice and bursting stage manner, and his songs such as “Pull It Up” and “Bonafide Love” remain a staple on American radio like Sirius-XM.

In the past year alone, music megastars Rihanna and Sean Paul have openly expressed support for him.

“Today I went to check Buju Banton, the great legend,” Sean Paul said in a video he posted online in October after visiting Banton at the McRae Correctional Institution in Georgia. “He’s in great spirits.”

Banton won his first and only Grammy on Valentine’s Day 2011. Less than 18 hours later, he was inside a Tampa, Florida, courtroom for the start of the federal trial against him.

“This case is a true miscarriage of justice, and it still keeps me up at night,” Banton’s trial attorney, David Oscar Markus, told ABC News in an email. “There was NO evidence to support the jury’s verdict.”

Pinellas County Sheriff Buju Banton is pictured in an undated booking photo from the Pinellas County Sheriff.

Prosecutors and a U.S. appeals court disagreed, with the court saying Banton “demonstrated familiarity with the drug trade” and deliberately laid the groundwork for a drug deal.

Banton — whose real name is Mark Myrie — did not respond to letters from ABC News seeking comment for this article. Spokesmen for the investigators and prosecutors declined to comment.

“A CHANCE ENCOUNTER”

The government’s entire investigation of Banton started with what both sides acknowledged was a “chance encounter” aboard an international flight.

“He had the worst luck that any of us could have,” Markus told jurors about his client.

Flying from Madrid to Miami after a European tour in July 2009, Banton happened to be seated next to a man named Alex Johnson. The two had never met, but as they both settled into the eight-hour flight, they began chatting and drinking together.

“We talk about women, we talk about cars,” Banton recalled at trial. “We were a bit loud … [We] were drinking immensely.”

At some point, for reasons that are still in dispute, the talk turned to cocaine. Banton claimed to have close ties to drug traffickers in the Caribbean — a claim investigators later found no evidence to support.

“We were both trying to impress each other,” as Banton remembered it in court.

Sitting beside Banton on the plane, Johnson boasted about his own ties to the international narcotics trade, describing himself as a Colombian “transporter” with a sailboat who can move drugs and money to the United States.

Johnson, however, was actually an ex-con who according to court records made millions of dollars working over 14 years as an informant for the Drug Enforcement Administration and other law enforcement agencies.

And Johnson had just found a new target.

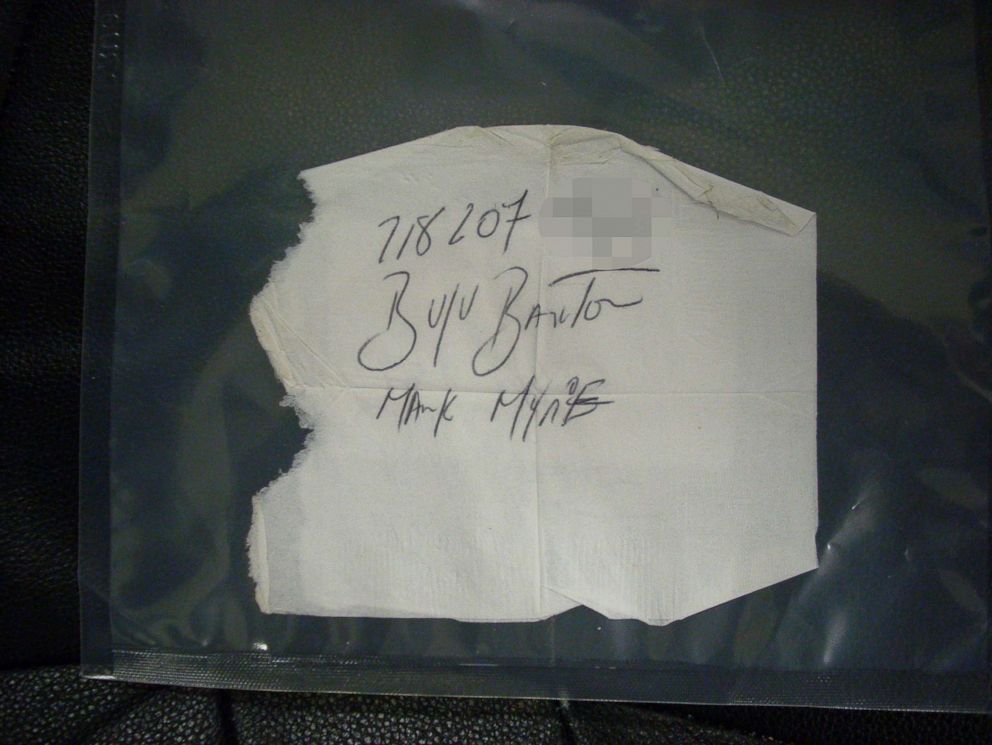

Before the plane landed, “[Banton] wrote his telephone number, his real name and artistic name on a napkin,” Johnson testified later.

Justice Department Government Exhibit 1 from the trial against Buju Banton.

“I NEVER DEAL”

In the week after they returned to Florida, Banton and Johnson met twice at restaurants in Fort Lauderdale, where they again spent several hours drinking and jabbering.

“I wasn’t there to discuss any drugs with Mr. Johnson,” Banton insisted during the trial, saying he simply found Johnson engaging and fun.

But with Johnson’s prompting, the pair rambled through grandiose ideas tied to drugs.

Johnson wanted to join forces with the Caribbean dealers Banton claimed to know; Banton proposed their own operation, buying low-priced cocaine in Colombia and smuggling it into Europe. Johnson suggested hiding cocaine in seafood shipments and paying off European customs officials.

Throughout the chatter, Johnson repeatedly pressed Banton to come see his sailboat in Sarasota, calling it an “important” step in their endeavor.

Banton, meanwhile, had his own message to emphasize: “I never deal. I’m always an investor.”

Though the reggae star had money to provide, he didn’t want to be the one meeting with buyers or sellers, Banton told Johnson. “I stay on the outside,” he said in a secretly-recorded conversation.

HEAR BANTON TALK ABOUT “STAYING ON THE OUTSIDE”:

Banton and Johnson never settled on a plan that first week, and they parted ways agreeing to stay in touch.

Over the next five months, however, their communications stalled. Recorded phone calls from the time, since released by authorities, indicate that while Johnson repeatedly reached out to Banton, asking to meet or otherwise catch up, Banton wasn’t as eager to reconnect.

Oftentimes Banton told Johnson he was too busy or too tired to meet.

HEAR BANTON PUT OFF JOHNSON:

In a September 2009 phone call, Buju Banton told DEA informant Alex Johnson he would be in touch later.

“For five months you’ve been trying to get him over to see you, and for five months he has either canceled or said, ‘No’?” Markus asked Johnson at trial.

“Yes,” Johnson conceded.

As Banton later described it, Johnson “was always pushing me to come, pushing me to come and see him, always calling me, but I would not go. … I stayed away from him.”

“A GUILT TRIP”

So that December, Johnson tried a different tactic.

Shortly after lunchtime on Dec. 4, 2009, Johnson called Banton to announce he had flown to Florida from out of town to see him. Having traveled so far, Johnson implored Banton to drive the two hours to Sarasota and finally see his sailboat.

“Make an effort,” Johnson told Banton in a recorded phone call. “It’ll all be worth it.”

Recalling the conversation during trial, Markus bluntly asked Johnson: “You’re giving him a guilt trip, right?”

“I am,” Johnson admitted. “I’m doing my job,” he said. The DEA and local police paid him more than $50,000 for his work on the Banton case.

Nevertheless, the tactic worked — Banton agreed to meet him in Sarasota. Banton also decided to bring with him a longtime friend, Ian Thomas, who Johnson was told could help procure large amounts of cocaine.

“What you told [Banton] is he was coming to see your boat?” Markus later asked Johnson.

“Absolutely right,” Johnson responded.

Driving together through the streets of Sarasota on Dec. 8, 2009, Banton and Johnson renewed their detailed talk of cocaine prices and a potential deal. Johnson even offered Banton a small stash of cocaine from the deal that the musician could sell on his own.

“Thank you very much for this opportunity man,” Banton told Johnson in the car, as he described an array of financial woes. “Oh you have given me opportunity to be myself again.”

But instead of taking Banton and Thomas to see his boat, Johnson brought them to a warehouse.

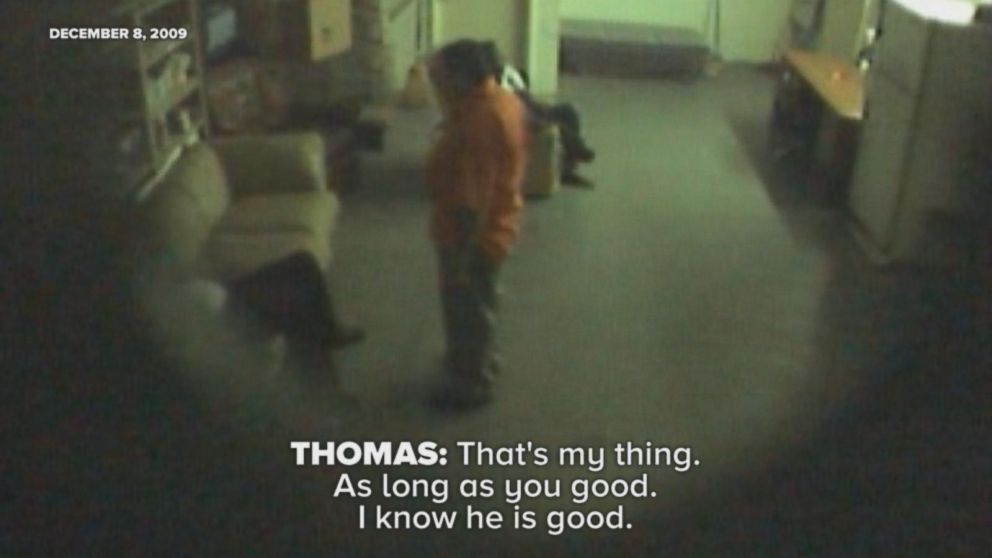

PHOTO: Surveillance video shows Buju Banton and others inside a Sarasota, Fla., warehouse on Dec. 8, 2009.

THE WAREHOUSE, AND THE VIDEO

The warehouse was owned by the Sarasota Police Department, and it had been outfitted with four hidden cameras.

When Banton and Thomas walked into the warehouse, Johnson introduced them to an undercover police officer, posing as a drug supplier.

“While you’re in here, I want to show you some goods,” Johnson told the others.

He had hidden 20 kilograms of cocaine in the back of an SUV. He pulled out one brick of the drug and handed it to Thomas, who walked the package to a nearby table.

Banton followed Thomas to the table and stood next to him for a full minute, while Thomas cut into the cocaine.

“You like it?” Johnson asked Banton.

“I like it,” Banton responded.

Seconds later, Banton slapped a dash of the cocaine onto his tongue to taste it.

WATCH BANTON INSIDE THE WAREHOUSE:

On Dec. 8, 2009, Buju Banton was caught on camera inside a Sarasota, Florida, warehouse.

“I don’t know why I did that,” Banton later said about tasting the cocaine. “If I could rewind the hands of time, I wouldn’t have done that. But I did.”

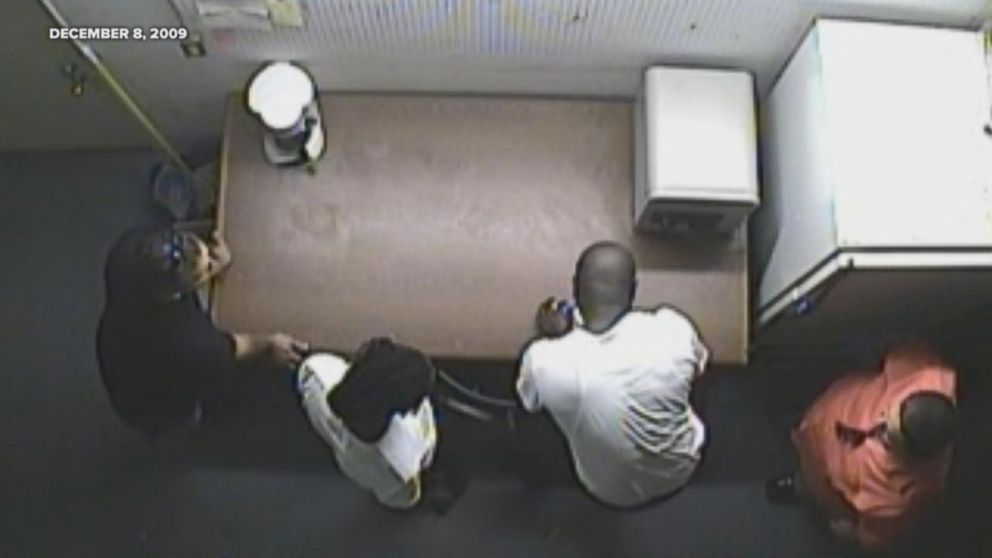

Shortly after Banton tasted the cocaine, Thomas got on the phone with a contact in Georgia who was looking to buy cocaine.

Banton chimed in from a chair: “Find out how much he wants.”

The Georgia man didn’t give a concrete answer, but he was clearly interested in buying what Johnson and Thomas had to offer. Banton told Johnson and Thomas to “trust” each other as they move forward.

WATCH BANTON TALK ABOUT “TRUST”:

On Dec. 8, 2009, Buju Banton was caught on camera inside a Sarasota, Florida, warehouse.

Banton then left Sarasota for his home in Tamarac, Florida, outside Miami.

Video from inside the warehouse was played during Banton’s trial and then sealed by the court indefinitely. U.S. officials objected to its release because it contained images of an undercover detective and a confidential informant, but after arguing in a letter to the court that the public had a right to see the video, ABC News persuaded a judge to unseal it.

Despite what the video showed, authorities said they were not prepared to take anyone into custody on the day of that warehouse meeting.

“The deal was still not finalized at that point, correct?” Markus asked Johnson at trial.

“That’s correct,” Johnson said, acknowledging the deal was still being negotiated.

THE FINAL DEAL

The day after the warehouse meeting, while Banton was at his home more than 200 miles away, the Georgia man came to a final agreement with Johnson and Thomas: He and an associate would buy five kilograms of cocaine for about $135,000, and they would send a crony named James Mack to Sarasota to make the exchange.

Thomas was to make $10,000 from the deal. It was unclear what — if anything — Banton would get out of it, according to Markus.

After all, even investigators conceded that the specific deal was reached without Banton’s knowledge, and Banton had no connection to Mack or the other Georgia men.

On Dec. 10, 2009, while Banton was asleep at his home, Mack, Johnson and Thomas convened at the warehouse in Sarasota.

Thomas brought $135,000 to hand over, and Johnson had a little bag with several kilograms of cocaine in it.

Seconds after Mack tested the cocaine, police stormed the warehouse and placed Mack and Thomas under arrest. Banton was then arrested at his home.

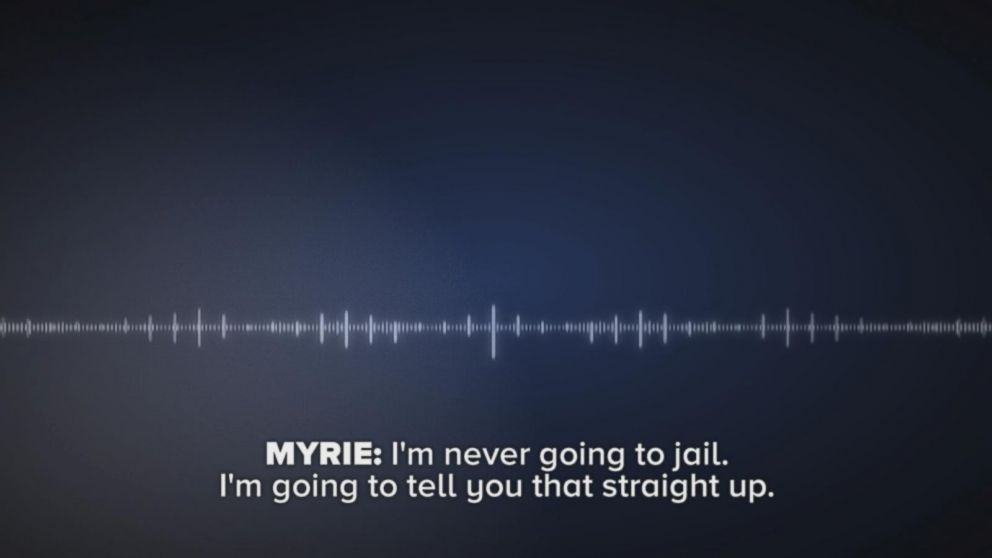

“I’M AN INNOCENT MAN”

Mack and Thomas quickly pleaded guilty to drug-related charges and have since been released from prison — though Thomas was back in police custody in February for allegedly trying to sell cocaine again.

In 2011, Banton was convicted of two counts for taking part in a conspiracy to sell cocaine, and despite his efforts to overturn the conviction, a federal appeals court later ruled “the evidence on the record supports” the jury’s conclusion.

As prosecutor Jim Preston described it during trial, once Banton introduced Johnson to Thomas, “the defendant’s role changed from that as an investor to that as a broker, bringing people together for a drug deal.”

The law is clear, according to what U.S. District Court Judge James Moody told jurors before they began deliberating.

Even if Banton “played only a minor part in the plan” but “willfully joined in the plan on at least one occasion, that’s sufficient for you to find the defendant guilty,” Moody explained.

Moody said “there is no entrapment” in a case when “the government merely provides what appears to be a favorable opportunity for the defendant” to “commit a crime the defendant was already willing to commit.”

“But,” Moody added, “if there is a reasonable doubt about whether the defendant was willing to commit the crime without the persuasion of [the] government … then you must find the defendant not guilty.”

Markus still insists there is such reasonable doubt.

Johnson “relentlessly pursued” Banton and wouldn’t “stop trying to turn him into a drug dealer even though his target repeatedly said no,” Markus told ABC News.

During the trial, Banton called Johnson “a master” manipulator who “staged” interactions “to destroy my life.”

“I talked the talk but I did not walk the walk,” Banton insisted at trial. “I did not take any action furthering the [deal]. I did not give him any money. I did not send him anywhere. I did not accept anything from him. It was all just talk.”

“I’m here today for running my mouth,” Banton added. “I’m an innocent man.”

At one time, many jurors agreed.

Banton was actually first put on trial in 2010, but a mistrial was declared after the jury couldn’t agree on a verdict. According to Markus, jurors voted 9-3 to acquit Banton.

VALUE OF THE VIDEO

For some, their support of Banton is unwavering, even when confronted with the undercover surveillance video from inside the Sarasota police warehouse.

Reggae star Stephen Marley, son of Bob Marley, testified for the defense in both of Banton’s trials, describing Banton as a “voice of the world” who never expressed interest in trafficking drugs.

“Would your view of Buju Banton change if you saw a video of him inspecting a kilogram of cocaine and tasting it?” Preston asked Marley in the first trial.

“No,” Marley stated.

PHOTO: A brick of cocaine recovered from a Sarasota, Fla., warehouse after Ian Thomas cut it open.

Similarly, an attorney who helped represent Banton during some of his appeals, Imhotep Alkebu-lan, said such video of Banton would be a logical part of any government effort “to set him up” and “put him there with the cocaine.”

For others who’ve supported Banton, however, the undercover video could make a difference.

Nearly two years ago, as President Barack Obama was preparing to leave the White House, Philadelphia-area DJ Darryl Robinson petitioned the commander-in-chief to pardon Banton.

“He was being railroaded by people who had their own motives and agendas,” Robinson wrote in his petition, which garnered 1,969 supporters. “Please find it in your heart to forgive and free an innocent man.”

Robinson recently told ABC News he followed Banton’s case through news accounts, and he believes Banton was targeted over long-festering allegations that the reggae star harbors anti-gay sentiments and promoted attacks on gay men in a decades-old song.

The allegations made national headlines in 2009 after gay-rights groups organized protests against Banton and concert promoters then canceled several of his U.S. tour dates.

Banton has denied subscribing to any such beliefs.

Robinson, however, did not know the federal investigation of Banton yielded secret recordings and undercover video, and when ABC News told him about the recordings he said they “would change my view.”

“You got caught red-handed, you are supposed to do the time,” Robinson said.

“LONG WALK TO FREEDOM”

Banton has now done the time — he has served his sentence. And he will be released from prison on Dec. 8, 2018, exactly nine years to the day since he was caught on camera inside a Sarasota warehouse.

“Many individuals would have wilted under the injustice of this case, but not Buju,” Markus told ABC News. “He is stronger than ever and is ready to show the world the wonderful music he has been working on.”

Once he is released, he will be deported to Jamaica, U.S. authorities said. And Banton has reportedly started booking shows in the Caribbean for spring 2019, when he kicks off his new “Long Walk to Freedom Tour.”

WATCH THE FULL VIDEO OF BANTON AND THE OTHERS INSIDE THE WAREHOUSE ON DEC. 8, 2009:

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.